Hoyle and Wickramasinghe's Analysis of Interstellar Dust

Almost always the men who achieve these fundamental inventions of a new paradigm have been either very young or very new to the field whose paradigm they change. — Thomas Kuhn

The astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle was born in Bingley, Yorkshire, England on June 24, 1915. He received a master's degree from Cambridge in 1939 and was elected Fellow, St. John's College, Cambridge in the same year. He rose to become Plumian Professor of Astrophysics and Natural Philosophy in 1958. He was a leading contributor in the discovery of how the elements from lithium to iron are synthesized inside stars. In 1997 he was awarded the Crafoord Prize by the the Swedish Academy in recognition of outstanding basic research in fields not covered by the Nobel prize.

Professor N. Chandra Wickramasinghe was born in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on January 20, 1939. He studied astrophysics at Cambridge, where he was a student of Hoyle's. He received his Ph.D. in 1963 and an Sc.D. in 1973, and served on the faculty at Cambridge. He later became a Professor of Applied Mathematics and Astronomy at the University College, Cardiff, Wales. He is an expert in the use of infrared astronomy to study interstellar matter.

These two scientists did not originally set out to prove that life comes from space. They were astronomers, not biologists. They were trying to identify the contents of interstellar dust by finding something that would match its infrared signature, or extinction spectrum. When they began working on this problem in the early 1960s, the standard theory was that the spectrum could be adequately explained by graphite grains. But an imperfect match between the theoretical and actual spectra, and an implausible account of the formation of the grains pushed Hoyle and Wickramasinghe to search elsewhere. In their work and others', molecules that are more closely related to biology began to enter the picture.

In 1968, polycyclic aromatic molecules were detected in interstellar dust (4). In 1972, convincing evidence that the dust contained porphyrins was obtained (5). Then in 1974, Wickramasinghe demonstrated that there are complex organic polymers, specifically molecules of "polyformaldehyde", in space (6). These molecules are closely related to cellulose, which is very abundant in biology. By 1975, Hoyle and Wickramasinghe were convinced that organic polymers were a substantial fraction of the dust. This line of thought was considered wildly speculative at that time. Now however, the idea that organic polymers in space are abundant and may be necessary for life is well accepted. Today we often see stories about things like vinegar among the stars (7), or "buckyballs" from space as "the seeds of life" (8). To that extent the scientific paradigm for the origin of life on Earth has already shifted.

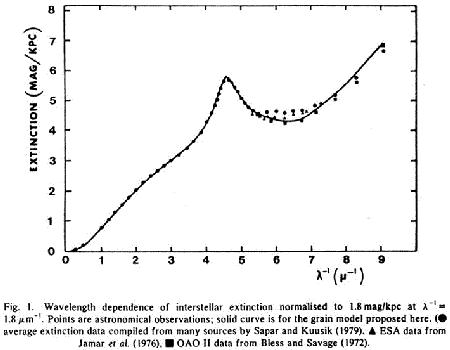

But Hoyle and Wickramasinghe were not satisfied. In the middle 1970s, they turned their attention to an apparent anomaly in the spectrum. It had a low, broad "knee" centered at about 2.3 wavelengths per micrometer (the slight convexity on the slope at the left side of the graph above) This spectral feature could be explained if the grains of dust were of a certain size, and translucent. After trying almost everything else first, in 1979, they looked at the spectrum for bacteria. Dried bacteria refract light as irregular hollow spheres, and their size range is appropriate. The match between the spectrum for dried bacteria (solid line) and the ones from the interstellar grains (dots, triangles and squares) was nearly perfect. Thinking without prejudice, Hoyle and Wickramasinghe concluded the grains probably were dried, frozen bacteria .

By Brig Kluce

From panspermia.org

No comments:

Post a Comment